Introduction au capitalisme de surveillance

Fondamental :

L'industrie numérique prospère grâce à un principe presque enfantin : extraire les données personnelles et vendre aux annonceurs des prédictions sur le comportement des utilisateurs. Mais, pour que les profits croissent, le pronostic doit se changer en certitude. Pour cela, il ne suffit plus de prévoir : il s'agit désormais de modifier à grande échelle les conduites humaines.

Les premiers mots de Propaganda d'Edward Bernays (1928)

Impossible d'accéder à la ressource audio ou vidéo à l'adresse :

La ressource n'est plus disponible ou vous n'êtes pas autorisé à y accéder. Veuillez vérifier votre accès puis recharger la vidéo.

Transcription textuelle

Bernays, Edward. Propaganda : Comment manipuler l'opinion en démocratie. Zones., 2007.

Timmerman, Julie, Mathis Buis, Karine Chambefort-Kay, Florence Jamet-Pinkiewicz, Stéphane Resche, et Nicolas Taffin. Un démocrate : Edward Bernays, petit prince de la propagande. C&F Éditions., 2020.

Leipold, Jimmy. Propaganda, la fabrique du consentement. Arte, 2018. [film].

Fondamental :

Exemple :

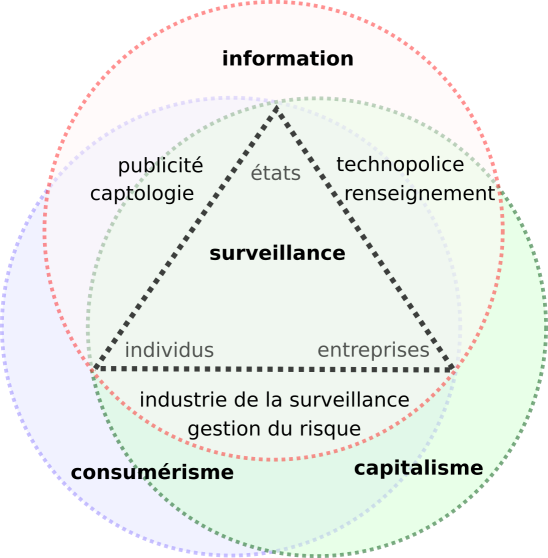

Les banques et assurances s'appuient sur les données pour gérer les risques.

La publicité s'appuie sur les données pour influencer les comportements.

Les états mobilisent les données pour surveiller leurs territoires.

Complément :

Currently, the predominant business model for commercial search engines is advertising. The goals of the advertising business model do not always correspond to providing quality search to users. For example, in our prototype search engine one of the top results for cellular phone is "The Effect of Cellular Phone Use Upon Driver Attention", a study which explains in great detail the distractions and risk associated with conversing on a cell phone while driving. This search result came up first because of its high importance as judged by the PageRank algorithm, an approximation of citation importance on the web [Page, 98]. It is clear that a search engine which was taking money for showing cellular phone ads would have difficulty justifying the page that our system returned to its paying advertisers. For this type of reason and historical experience with other media [Bagdikian 83], we expect that advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of the consumers.

Since it is very difficult even for experts to evaluate search engines, search engine bias is particularly insidious. A good example was OpenText, which was reported to be selling companies the right to be listed at the top of the search results for particular queries [Marchiori 97]. This type of bias is much more insidious than advertising, because it is not clear who "deserves" to be there, and who is willing to pay money to be listed. This business model resulted in an uproar, and OpenText has ceased to be a viable search engine. But less blatant bias are likely to be tolerated by the market. For example, a search engine could add a small factor to search results from "friendly" companies, and subtract a factor from results from competitors.